I AM Ai Weiwei: Human Flow

Production Still from Human Flow feat. Director, Artist, Activist—Ai Weiwei

Interview by Editor-In-Chief, Liberté Grace

“Creativity is the power to reject the past, to change the status quo, and to seek new potential. Simply put, aside from using one’s imagination—perhaps more importantly—creativity is the power to act.”

Ai Weiwei is a Chinese contemporary artist and activist who is considered one of, if not—the most influential artist—in the world today. Known for his life of rebellion: against everything from his childhood and adult experiences of government-controlled exile, to deliberately smashing a two-thousand-year-old ancient urn—Weiwei’s persistent call to freedom, has infamously led him to dangerous places.

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) By Ai Weiwei

Human Flow is no less characteristic of his disruptive and creative acts of rebellious sovereignty.

In his most personal documentary to date, Weiwei exhibits a different kind of rebellion; challenging the dehumanised media coverage of what is a growing global humanitarian crisis.

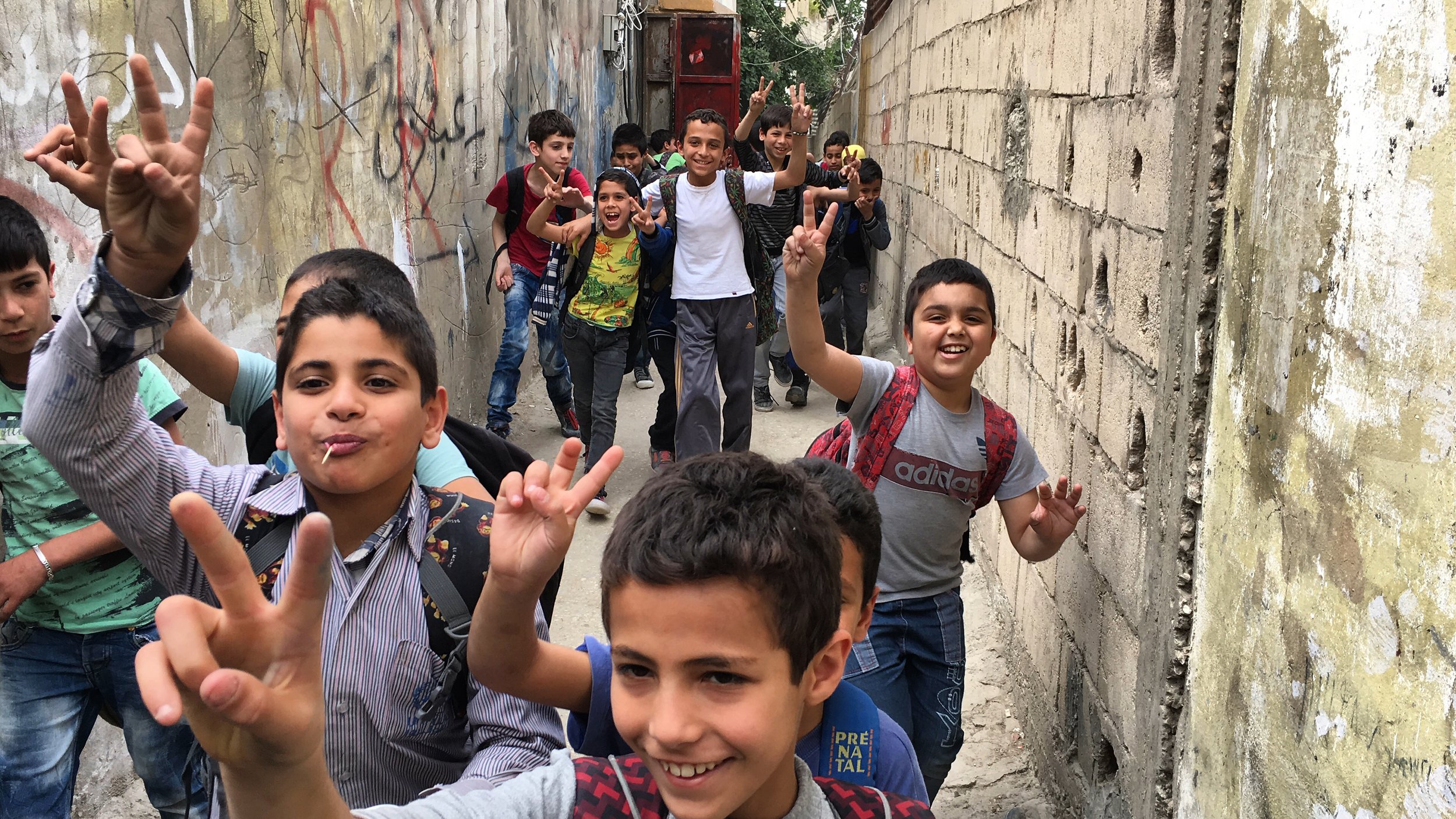

The film’s breathtaking drone footage provides beautiful, yet heart-breaking visual maps; tracing the magnitude of the growing refugee problem, that many countries have rejected any responsibility to solve. The intimate, often silent portraits of refugees he features; are birthed from an honest and unsentimental gaze of compassion, making them all the more confronting.

Each frame carries a stark reality check, that is difficult to reconcile in modern times. One cannot help but be moved by the many discarded humans Weiwei interviews and features; fighting to live in the face of closed borders and third-world conditions, after losing their homes and lives to the effects of war and global warming.

“It’s not a refugee crisis. It’s a human crisis.”

Human Flow Official Trailer - courtesy of Amazon Studios

The gift to its audiences is: a never-before-seen insight into the personal stories behind the hypocritical state of affairs in human culture today, which promotes compassion and freedom, in every sector from business to entertainment, but fails dramatically, to act on that compassion when responding to this growing human crisis—due to the prioritisation of political agenda, over valuing human life.

Human Flow was distilled from over 900 hours of documentary footage and Weiwei’s iPhone videos, after he travelled with his team to over 23 countries, 40 major refugees camps, and interviewed 600 refugees. The result is a stark, yet visually spectacular piece of cinematic poetry, which urgently invites its audience to care about the 65 million displaced refugees roaming the planet, without a home or recognition by any authority.

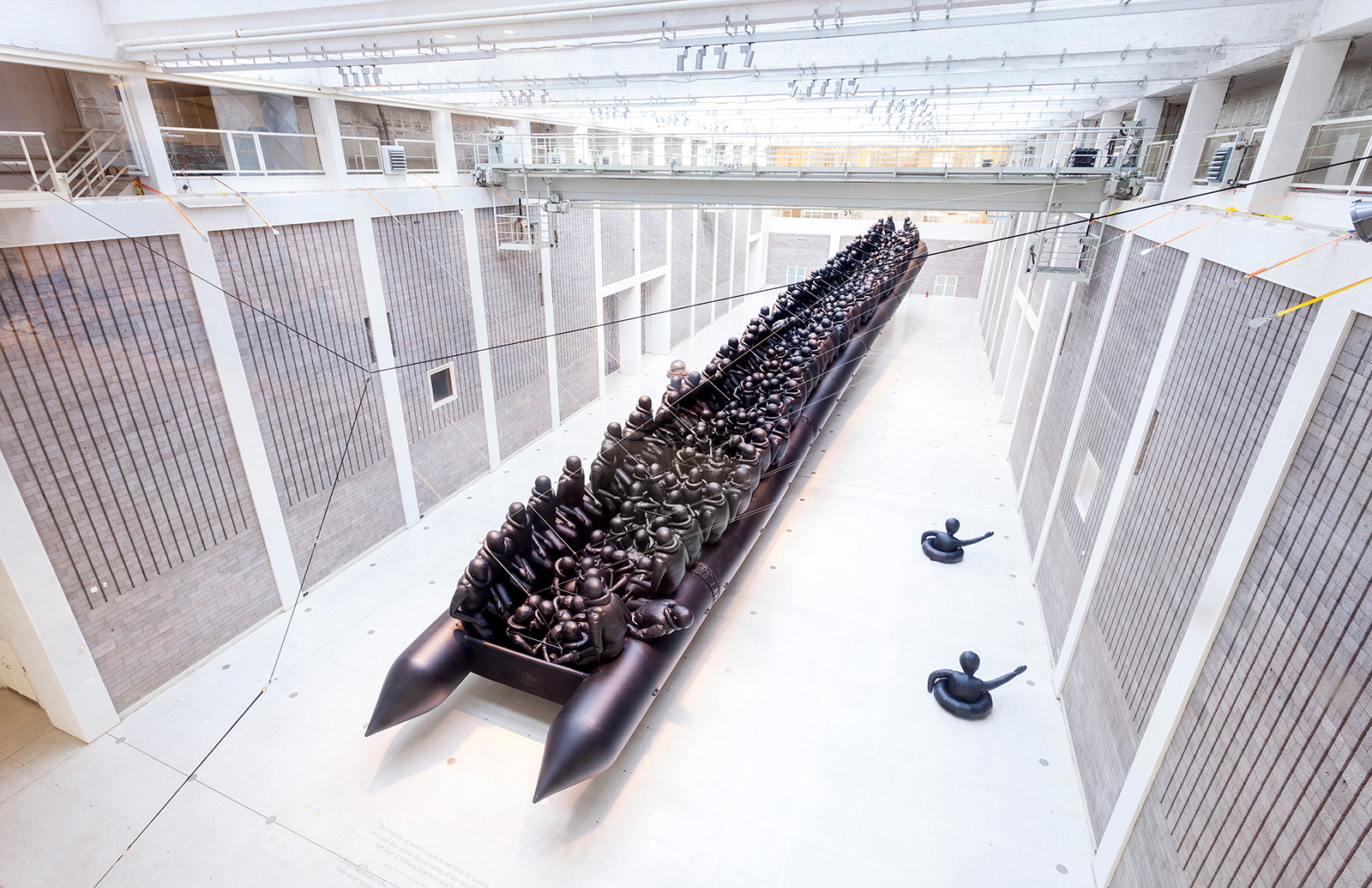

Law of the journey Ai Weiwei, National Gallery, Prague

Ai Weiwei recently attended premiere screenings of Human Flow in Sydney, Australia, as one of the key highlight attractions of the 21st Biennale of Sydney, also showcasing an accompanying installation work of a 61-metre refugee life-boat, entitled, Law of the Journey on Cockatoo Island from the 16th March - 11th June.

Here are some of the conversation highlights, hosted by Naomi Steer—National Director of Australia for UNHCR, who opened the discussion about Ai Weiwei’s first experiences of living like a refugee, as the son of famous Chinese dissident and poet, Ai Qing. From the age of 12-months-old, Weiwei experienced firsthand, the indignities of homelessness and being stripped of his identity when his family was exiled: after his father ran afoul of the Communist regime.

Could you talk about the circumstances around that time in your life?

AW: I was born in 1957. At that time in China, it was not like China today, but, very much like North Korea, or not even that. In North Korea today, you can be much more modern, than during that time (in China). So, I spent 20 years in (Shihezi) Xinjiang, near the Russian Border, in the furthermost location of north-west (China); where they sent my father. That was a tradition in Asia at that time—they always sent the poets or writers, in exile to a very far away (place), to make sure they could not come back. My father spent 18 years, in these kinds of conditions.

During the cultural revolution, it even got worse. It became a hard labour camp. That's basically, my early experience. And that's maybe the background to why I wanted to do this film. Because, my father, besides being highly poetic, he also cared about social justice, fairness, being honest, being valued— all those things that relate to very high human values of dignity.

So, I respect him very much regarding that, and maybe that gave me some kind of influence. But I didn't realise it until very late after he passed away when I got into so much trouble with the authorities. So, I had to ask myself, why had I become the person I am today? I think that early experience with my father had something to do with it.

Music video for Dumbass by Ai Weiwei. Song by Ai Weiwei with music by Zuoxiao Zuzhou. Cinematography by Christopher Doyle. ©2013 Ai Weiwei. From the forthcoming album, "The Divine Comedy."

After your family was able to return from their exile, they got a visa and passport and were able to travel. You were in New York for 12 years. How much did that influence you in becoming a Global citizen?

AW: I went to New York, and I was enrolled in Parsons School of Design. Half a year later, I dropped out because the tuition was too high. For someone who came from a communist society, it was very hard to understand why you would pay so much tuition for almost not much education. I hate education. My whole life, someone wanted to educate me. And for me, to pay tuition to be educated was not acceptable.

“So, I call myself an artist. That means: if you tell people you are an artist, they will not really ask what you do. It saves so much trouble. ”

Anyhow, time passed. I struggled in New York. It was not possible for me to get any kind of recognition. So, I totally gave up. I said: "Forget about art. I can do anything to survive. I'm capable." I had this kind of confidence.

And, 12 years later, I went back to China. By then, China had changed in many ways. It became capitalist. But, it was not true Capitalism. It was/is state Capitalism. The whole competition is made up by one party, one government, which controls everything. And they never give its people a chance to make decisions. They don't trust people. When you don't trust people, your legitimacy is not there. You only control the nation, because you have the army, the jail, and then you have the court, which is not independent. Within the judicial system; they manipulate every case.

But, they said, "Let's get rich first." Now, China is very rich, you know. And I heard, Australia's economy is also invested in China's business. China has become an important factor in globalisation.

In talking about making the film Human Flow, you came across many people with terrible journeys who were forced to make terrible decisions, when they were forced to flee. What did you find the most challenging in making Human Flow?

AW: Making this kind of film, came from my personal curiosity. I wanted to learn what this word, "refugee" really means. And that simple question lead me to a big project; where we travelled to 23 nations, visiting 40 of the largest camps, and interviewed over 600 people— resulting in over 900 hours of footage. It was such a struggle to get to know this subject.

And every nation, every location, is difficult, it's dramatically difficult. Some work is dangerous—you have Isis, you see the war zones—but those are easy to manage. The hardest thing is when you leave those people; women, children etc. You feel somehow you cannot do much to help them.

And that is very difficult to take when you're filming a documentary, because you feel, there's not much you can do to help to improve the situation.

“We know all the refugees in the world will spend on average 20 years as a refugee, so it’s like, generations are wasted.”

You use social media extensively, which explains why you have such a huge social media following, with so many young people. And here tonight, there are so many young people and those who are young at heart. Are you optimistic that the next generation will take down the barriers, that our generation has been building?

AW: I can say, hopefully. We are living in this globalisation world, and many many problems are caused by the older structure, the older way of thinking. Politics, for example, when you hear some politicians speak—doesn't matter where in the world—it's like that guy comes from death. It doesn't sound real in this modern society when you hear so many politicians. When they speak, you just shake your head as if to say, "Where is this guy coming from?"

But the younger generation; they are living in the internet age, with such a flow of information and exchange of ideas. Hopefully, the world will become much more (than it is). Justice should be achieved. There should be peace in the world and a better environment.

Human Flow is available to view online and at select cinemas worldwide. You can follow Ai Weiwei on Twitter and Instagram.

Donations can be made to UN Refugees at https://www.unrefugees.org.au/donate/#monthly

Follow I AM FILM on Instagram (iamfilmofficial) #IAMFILM and Join our list to receive news and views by the Masters of Film.

About the Artist

Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei (born 28 August 1957 in Beijing) is a Chinese contemporary artist and activist. His father's (Ai Qing) Ai collaborated with Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron as the artistic consultant on the Beijing National Stadium for the 2008 Olympics. As a political activist, he has been highly and openly critical of the Chinese Government's stance on democracy and human rights. He has investigated government corruption and cover-ups, in particular, the Sichuan schools corruption scandal following the collapse of so-called "tofu-dreg schools" in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. In 2011, following his arrest at Beijing Capital International Airport on 3 April, he was held for 81 days without any official charges being filed; officials alluded to their allegations of "economic crimes". [Source: Wikipedia]

His new documentary film Human Flow was nominated for a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival (2017) and won the: Fondazione Mimmo Rotella Award, Fair Play Cinema Award - Special Mention, CICT-UNESCO Enrico Fulchignoni Award, Human Rights Film Network Award - Special Mention, and Leoncino d'Oro Agiscuola Award - Cinema for UNICEF.